Contents

- What is the 3-2-1 rule, and why do some feel it is no longer enough?

- The 3-2-1 rule

- The rising pressure of technological progress

- Newer versions and alterations of the 3-2-1 backup strategy

- The 3-1-2 rule and the rise of cloud backups

- The 3-2-2 rule and the first successful alteration of the original strategy

- The 3-2-3 rule and the increasing role of offsite storage

- The 3-2-1-1 rule; the concepts of immutability and air gapping

- The 3-2-1-1-0 rule and the definition of backup testing

- Comparing the 3-2-1 backup strategy with its alternatives

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the biggest difference between the 3-2-1 backup rule and its variations?

- Is there a single backup strategy that can be considered the best for everyone?

- What are some of the best practices for better backup management alongside the 3-2-1 (or other) backup strategy?

What is the 3-2-1 rule, and why do some feel it is no longer enough?

The 3-2-1 backup rule (often referred to as “strategy” as well) has been one of the most essential pieces of advice in the field of data protection for multiple years now. In fact, many businesses that failed to adapt this best-practices strategy eventually came to regret it. Indeed, partly because of the misconceptions in the industry regarding safety of data in the cloud, some organizations continue to have a significant weakness in their backup strategy today. As a result, many will likely, unfortunately, pay the price sometime in the future.

The 3-2-1 rule

The original version of the 3-2-1 backup strategy was created by photographer Peter Krogh. It is also considered to be the expansion of the basic tape backup strategy (which involves taking a single copy of the media and storing it using tape storage, creating a second off-site data storage location for the backup).

Its description was extremely simple:

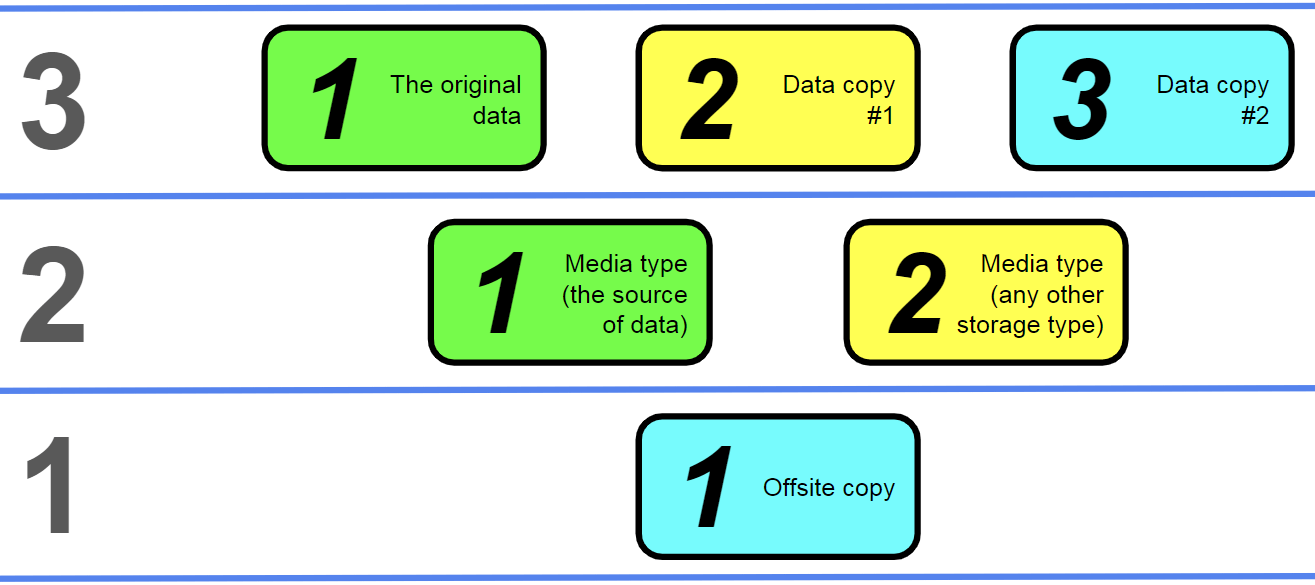

- There should always be three copies of data (counting the original version).

- These copies should be stored using two different storage media types.

- At least one of these copies should be stored off-site (physically and geographically separate from the rest).

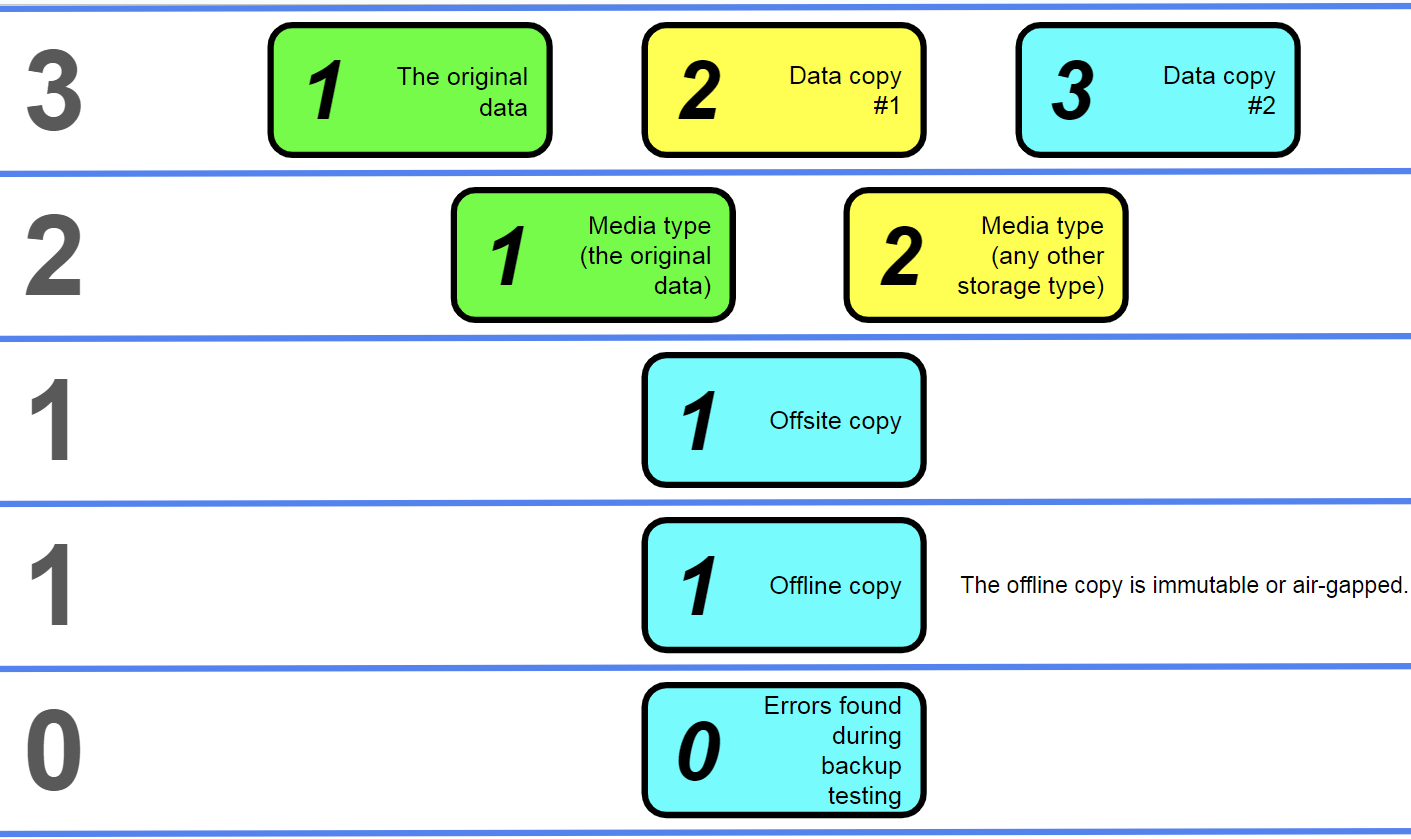

All of the graphics in this article are going to follow a similar pattern, with the name of the strategy being shown in the number form on the left side of the image. Each part of the strategy is presented as a separate category to simplify the visualization of different strategy elements.

This backup rule offers an impressive number of advantages to any user who does not have a structured backup strategy in place. It can mitigate multiple risks of data loss, improve the company’s capabilities in terms of disaster recovery, enhance data protection against hardware and software failures, and more.

The 3-2-1 rule is both simple and effective. It creates a protective net over the original data copy that protects it from natural disasters (off-site copy), accidental deletion or corruption (second copy alongside the original), etc. In fact, it had such an impact at the time that it was mentioned in one of the collaborative publications between the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the National Cybersecurity Center of Excellence (NCCoE) as a recommended data protection tactic.

The proven story and success of the 3-2-1 rule does not end there. The modern reality of data protection requires all protective measures to evolve and adapt over time to match the development pace of ransomware and other potentially disastrous types of software – and so it is with the 3-2-1 rule. Some of the notable, relevant changes in the IT world since the advent of the 3-2-1 rule are the development of the Cloud, and the increased danger from threat actors, malware and ransomware, and even the acknowledgement of increased risk of attack from a rogue person that is internal to the organization.

This is partly how several interpretations of this backup rule were born, including:

- 3-2-1-1

- 3-2-1-1-0

- 4-3-2

Of course, this list is far from conclusive and Systems Administrators may have their own variations. As such, it is our goal to explain the purpose and strategy behind each of the following backup rule variations while also debating whether there is a single backup strategy that is the objectively best option for everyone.

The rising pressure of technological progress

The technological world has evolved since the emergence of the 3-2-1 rule of course, for example with ever-larger data storage volume available, and the availability of Cloud service. However, with that has also arrived a more sophisticated range of considerations and even threats to an organization’s data – whether personal or corporate:

- The rise of newer, more efficient technologies, combined with the need to keep up the current state of legacy tech. The “sunk cost fallacy” of maintaining older storage types such as optical libraries or legacy tape drives can be extremely high and possibly not worth the resources it siphons from the budget. Note: this is not to say that modern tape is not useful. The truth is quite the opposite. Modern tape technology is far more advanced than many people realize, and typically far more sustainable than disk for high data volume.

- The exploding popularity of technologies such as deduplication can make storage space requirements for backups much lower. At the same time, deduplication can significantly increase the time (and risk) it takes to restore one such backup, which is why it might not be the best fit for businesses with demanding RTOs and RPOs.

- Another example is ongoing and increasing adoption of cloud storage, which makes perfect sense in the context of the 3-2-1 rule. Today, the cloud is often used as the “1” in the 3-2-1 rule (where it previously tended to be off-site tape). However, the security and true reliability of third-party cloud storage is extremely difficult to verify thoroughly, and it also spawns a number of its own issues – including bandwidth limitations, questionable redundancy models, and more.

- There is also the ever-growing threat of ransomware. This might just be the biggest reason of them all, considering how ransomware was at least 68% of all cyberattacks by the end of 2022. In this context, ransomware becomes something that is very difficult to ignore, and the traditional 3-2-1 tactic would not be enough to save a company from a more modern version of ransomware that can detect and encrypt backups before altering the original file copy.

Of course, this is but a fraction of all the new developments and technologies that can affect the effectiveness of a traditional 3-2-1 backup tactic. There are plenty of other issues that are not even that affected by the modification of the existing backup strategies – such as the necessity to manage hundreds and thousands of backups in the long run.

However, it serves as a great showcase of how the world is evolving at an alarming pace, which is why even the most basic recommendations have to evolve with it to stay relevant and effective.

Newer versions and alterations of the 3-2-1 backup strategy

Since the original 3-2-1 rule, there have been different variations of the theme that were utilized in some way since then. Some of these strategies are officially recognized to a certain degree, while others are mostly just a new explanation of existing technologies using familiar naming conventions.

The 3-1-2 rule and the rise of cloud backups

Variations of a traditional 3-2-1 backup strategy have been appearing for a while now, and not all of the options are considered variations. For example, the rise in popularity of cloud-based storage providers led to the vast expansion of the so-called 3-1-2 backup rule.

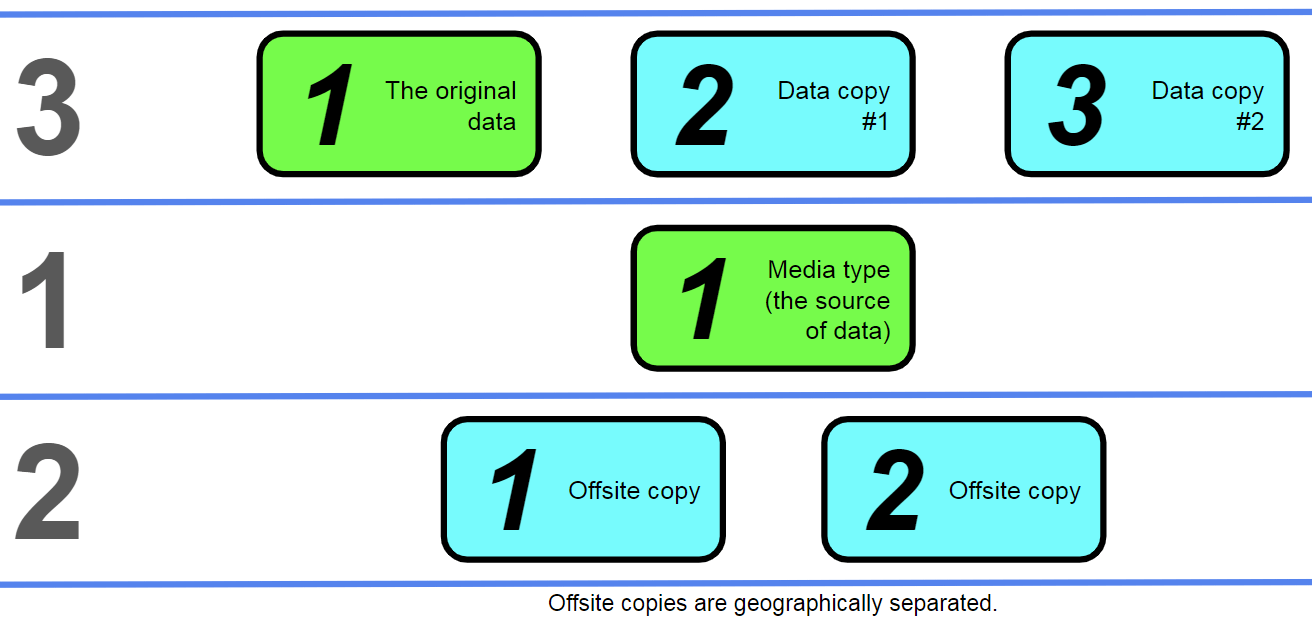

Following the same naming convention as before, the 3-1-2 backup rule still creates three backup copies but only uses a single known media type (the original version of the data stored on disk or in some other way) and creates two offsite copies.

In these scenarios, the ephemeral “cloud” cannot be considered a media storage type (since not all of the cloud storage providers share this kind of information), which is why it is not counted in the “name” of the strategy.

It is important to mention that not all cloud storage providers can store a client’s information in two geographically separate locations, and this kind of topic should be verified on a case-by-case basis.

There have been requests by cloud users for the cloud storage providers to provide two different copies of data as a lack of trust in their security measures. However, that is far from the truth, as the geographical separation is a great safeguard against both natural and manufactured disasters that the cloud storage provider would not be capable of stopping in any way.

The 3-2-2 rule and the first successful alteration of the original strategy

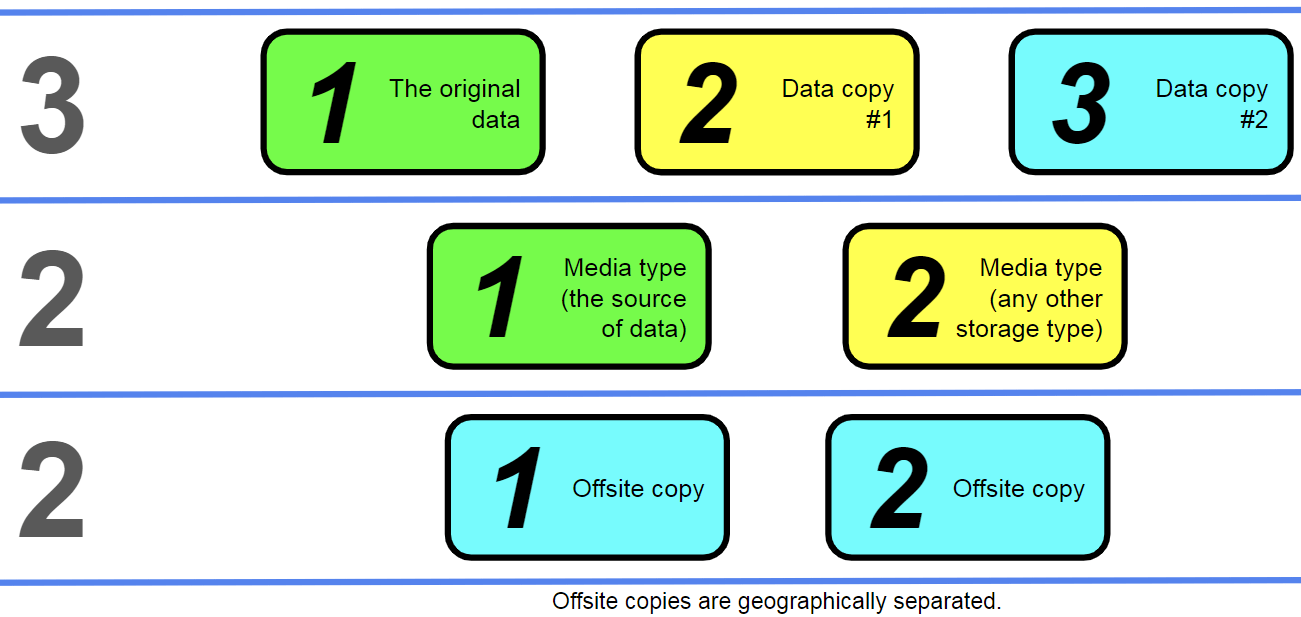

Following a similar evolution logic for the existing backup rules and strategies, we can also review the 3-2-2 rule.

This is where the naming convention becomes somewhat debatable. The existence of a second media type in the context of the 3-1-2 rule implies the existence of a fourth data copy that would be stored on that media type, which makes the statement about “three copies” in a strategy’s name somewhat misleading.

In this case, naming this backup strategy “4-3-2” instead of “3-2-2” may be more accurate. However, this kind of naming convention strays too far from the original idea of a simple name with a simple meaning, which is why this strategy will be referred to as “3-2-2” for the purpose of this blog.

The 3-2-2 backup strategy can be considered the modernized version of the original 3-2-1 approach since it creates a comfortable network of backup copies and storage types to work with while also using more modern technologies such as cloud backup. The ability to use either the cloud copy or the local copy of a company’s data adds versatility to this setup while also improving continuity and retention in the process.

The 3-2-3 rule and the increasing role of offsite storage

The aforementioned 3-2-2 backup rule can also have its own variation of sorts, with the addition of a manually created offsite copy that uses the second media device introduced above to move the copy out of the company’s premises. This is how the 3-2-3 backup rule is born.

It does make the backup renewal process somewhat more convoluted, and the addition of a manual offsite copy creation makes the process even more sophisticated, but the end result of a backup strategy that can restore from three different offsite locations for disaster recovery purposes is an advantage that is big enough for some companies to consider it worth the effort.

It should be mentioned at this point that examples such as “3-2-3” are simply extensions of the same logic as the “3-2-1”, and may seem superfluous to some. In all fairness, most of these backup strategies do not even have to be named in the first place since many of them can be considered redundant expansions of the original formula without needing the renaming process. Nevertheless, we are now going to highlight more examples of backup rules that have developed from the 3-2-1 rule that are currently being discussed in the industry.

The 3-2-1-1 rule; the concepts of immutability and air gapping

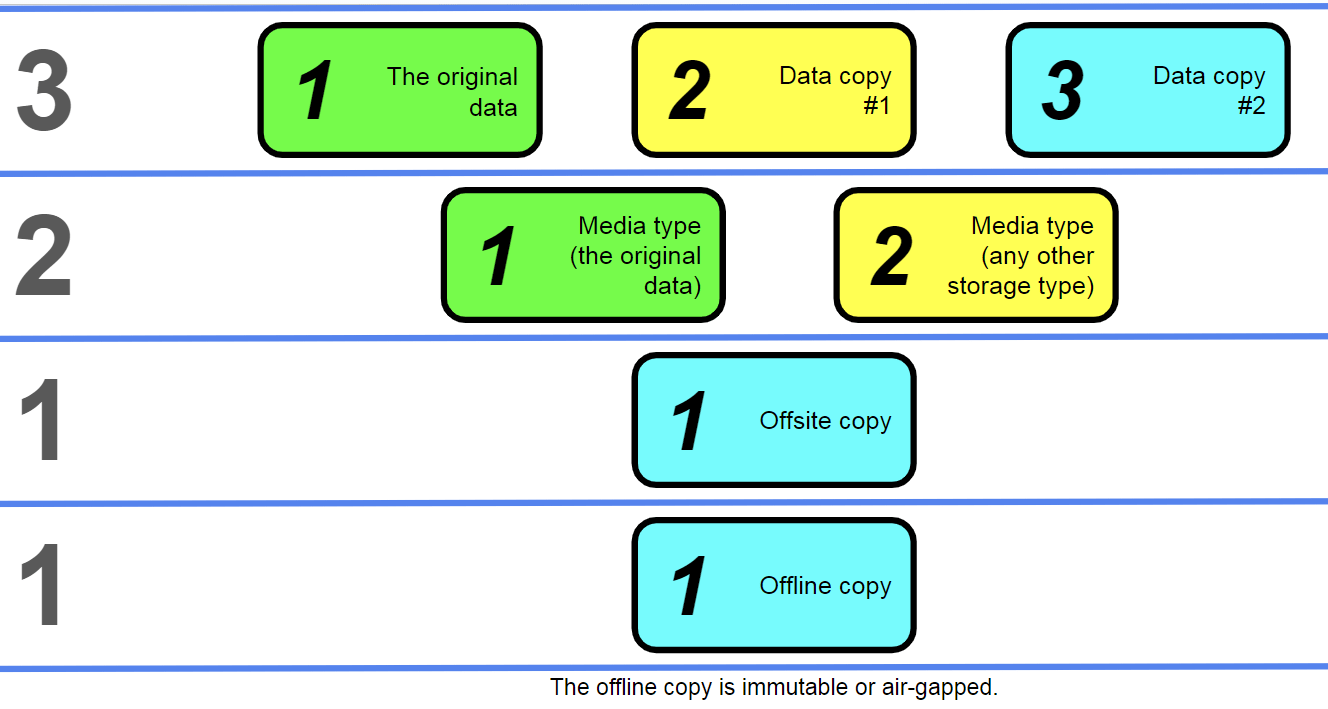

The 3-2-1-1 backup strategy can be considered the first “official” alteration of the original rule since it is officially recognized by a number of different backup solutions, such as Acronis. This strategy’s main difference is its addition of immutability to the existing formula.

Following the same naming convention as mentioned above, it is not that difficult to understand that the 3-2-1-1 strategy is just a 3-2-1 strategy with an additional requirement: one immutable or air-gapped data copy.

There is a lot of confusion in the industry when it comes to differentiating between immutability and air gapping. Since this is not the primary topic of this article, we are only going to provide a short explanation of the two terms.

Immutability is the property of data that prevents it from any kind of modification after being written. Air gapping is the practice of physical separation between the backup (and its storage unit) and the rest of the connections, including both internal and public networks. The idea of physical separation is so that the separated media cannot possibly be hacked or accessed remotely.

Immutability is much easier to set up on the software level, and its primary purpose is to ensure data integrity and offer ransomware protection. However, by its very nature, it may be possible – because the software is likely to have a physical connection – that it could be compromised. Air gapping is perhaps more difficult to maintain, and a result is not especially popular outside of extremely sensitive data – critical infrastructure, classified government information, etc.

Both immutable and air-gapped backups offer an impressive level of security, even if they have their own respective shortcomings. In the modern environment, it is not that easy to find a backup solution or a cloud storage provider that offers true data immutability by default, which makes it a lot easier for the client’s data to be corrupted or deleted in its entirety.

The 3-2-1-1-0 rule and the definition of backup testing

Following many previous examples, we arrive at the latest variation of the 3-2-1 backup strategy or rule. The 3-2-1-1-0 backup strategy uses the same framework from the 3-2-1-1 rule while also adding the concept of backup testing to the mix (while also putting more emphasis on air-gapped backups instead of immutable ones for better overall security).

While backups have proven to be very useful tools in the context of data restoration and disaster recovery, they are also prone to failure, and there can be many different reasons why a specific backup might not be able to restore itself when necessary.

As such, all backups also have to be tested on a regular basis to ensure their current state and to fix any potential issues before anything happens. The idea of backup testing and data monitoring has been around for a long while of course, but it was spontaneous at best for many years before eventually becoming practically mandatory for many backup solutions and infrastructures.

In the modern world, backup testing is one of the common parts of a company’s business continuity and disaster recovery plan – and at least one of the aforementioned backup rules should also be included in all these plans. The 3-2-1-1-0 strategy sets in stone the necessity to perform regular backup testing operations, improving the security and resilience of all systems that decide to adopt this backup strategy.

Comparing the 3-2-1 backup strategy with its alternatives

While it is true that practically every single one of these backup rule variations has its fair share of reasoning and advantages behind it, summarizing them here would be a helpful conclusion to this article.

As such, here is our short explanation of the 3-2-1 rule and all of its major derivatives:

- 3-2-1 rule – the original basic backup strategy. It still works extremely well, and organizations that do less than this would be well advised to reconsider, despite what some backup vendors would have their customers believe.

- 3-1-2 rule – a variation of the original backup plan that uses the cloud storage solution to store both of the backup copies in separate locations. Please see the comment above for the 3-2-1 rule;

- 3-2-2 rule – simply an explicit variation of the 3-2-1 rule.

- 3-2-3 rule – a relatively small extension of the previous rule that stores the second media storage copy in an offsite location;

- 3-2-1-1 rule – a first “popular” variation of the 3-2-1 rule that adds backup immutability/air gapping to the original rule set;

- 3-2-1-1-0 rule – an extension of the 3-2-1-1 rule that introduces the concept of frequent backup testing to the mix.

Conclusion

While the traditional 3-2-1 backup strategy is probably more necessary than ever before, some organizations are responding to the current environment by looking for ways to further build on it to protect themselves even more.

It is likely not necessary for some companies to have to go beyond basic 3-2-1, as this basic rule continues to prove to be highly effective. In this context, the only piece of advice we can give is to analyze your own risks and pick the strategy that fits your company’s needs the most.

The total number of different variations of the 3-2-1 rule is very difficult to quantify since some are not well documented. However, it does show that 3-2-1 managed to become a universally accepted best-practice and standard framework for backup strategies.

In general, it would not be a good idea to recommend one single backup strategy from this list for all. For example, backup immutability is typically a requirement in the context of some regulatory frameworks, which may make the usage of the 3-2-1-1 rule practically mandatory in those cases– and this is just one of many examples that might not be completely optional for specific user groups.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the biggest difference between the 3-2-1 backup rule and its variations?

Most of the variations of the 3-2-1 strategy use it as the baseline and add features or capabilities on top of it. There are a few exceptions to this rule, but all of the “officially recognized” backup strategies are just more specific versions of the 3-2-1 framework that has remained practically unchanged over the years.

Is there a single backup strategy that can be considered the best for everyone?

The backup strategy that came close to being considered universal for everyone was the 3-2-1 strategy at the time of its inception. Using it as a baseline strategy is highly recommended by Bacula. As an extension of that, the 3-2-1-1-0 strategy is an example of a strategy likely to withstand a lot of different threats, but it may also be the most difficult and expensive of them all, which makes it impractical for a lot of SMBs.

What are some of the best practices for better backup management alongside the 3-2-1 (or other) backup strategy?

- Backups should be performed at regular intervals.

- Backups should be automated.

- The topic of backup media types should be approached with preparation and sufficient research.

- Recovery speed should be tested regularly to correct existing RTOs and RPOs if necessary.

- Employees should be aware of the existing backup practices and instructed on how to follow the basic rules of cyber hygiene.